PHOTO

*Copy_Boyd Cordner_Image001_54617

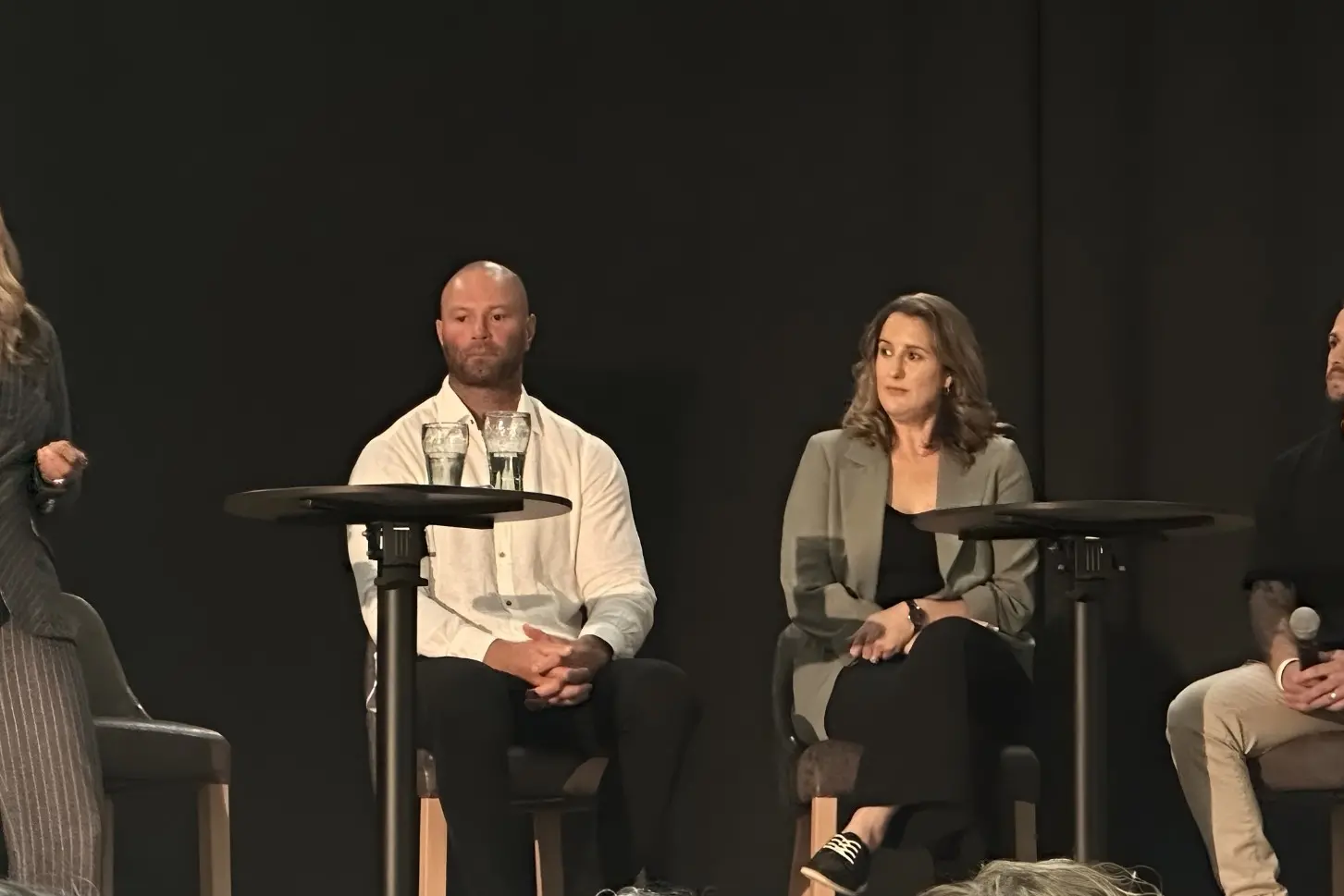

Former NRL captain Boyd Cordner opened up about loss, resilience and mental health during a heartfelt community event in Young on Friday, October 31.

Hosted by Young Medicare Mental Health Centre and the Hilltops Suicide Prevention Network, Teamwork: An Evening with Boyd Cordner on Mateship and Mental Health featured Cordner alongside psychologist Edwina Planten and Rhys Cummins from Murrumbidgee Men’s Group, sharing messages about vulnerability and strength.

Cordner began by reflecting on the loss that shaped his childhood.

“I lost my mother to breast cancer when I was four years old,” he said.

“From a young age, I sort of grew up without a mother.”

“It was only us three boys, my dad, my older brother, and me.”

He also recalled losing his grandfather, a central figure in his life.

“Pop was one of the hardest men I’ve ever known… when he passed away when I was 10, it broke me.”

Those early experiences, he said, built the mental toughness that carried him through football.

“The resilience I had to learn at a young age taught me the tools I needed to face whatever challenges came my way.”

His mother’s memory became his lifelong motivation.

“Everything from then on, all I wanted to do was make her proud,” he said.

“She was my biggest ‘why.’”

“If you have a strong why, you’ll get through anything.”

Cordner retired from the NRL in 2020 at just 28 after repeated concussions, a decision that triggered deep emotional turmoil.

“When I retired at 28, that’s when the mental battle really started for me,” he said.

“I’d had concussions before, but this time the headaches never went away.”

“I couldn’t sleep, the pressure in my head was killing me.”

“Scans came back saying my brain was perfect… but I wasn’t.”

At the time, Cordner was captain of the Sydney Roosters, the New South Wales Blues and the Australian Kangaroos.

“I was driving my car and broke down crying for no reason.”

“The noise, the ringing in my ears, it just wouldn’t stop,” he said.

“Physically, they told me I was good, but mentally my body was saying something different.”

“I had to sit and ask myself some hard questions.”

“I was scared of what the next head knock would bring.”

“That’s when I knew it was time to retire.”

Known for his toughness, Cordner admitted he struggled to seek help.

“I always thought I was mentally strong enough to deal with anything… until I wasn’t,” he said.

“It wasn’t until I saw a psychologist that I realised how much I’d been holding in, retirement, personal issues, things from the past.”

“It all piled up.”

Therapy and medication, he said, helped him rebuild.

“Getting help didn’t change who I was.”

“It just helped me think clearer and unpack what was weighing me down.”

“It’s not a weakness to take medication or talk to someone.”

“Sometimes you just need help to straighten things out.”

Cordner urged compassion for those struggling.

“You don’t have to have all the answers, just be a safe space for that person.”

“Sometimes all people need is for someone to listen.”

To young people, his message was simple, saying, “have the courage to speak up, even if it’s not to a professional, talk to someone you trust.”

“If someone comes to you, don’t judge, just listen.”

“You’ve probably been through something yourself and wished someone did the same for you.”

Mental health, Cordner said, has touched his own family deeply.

“My brother tried to take his life, my cousin did too… I’ve seen firsthand how important it is just to be there for someone.”

“Sometimes you can’t fix it, you just have to be there.”

After retiring, Cordner struggled to find purpose without football.

“When football was taken away from me, I felt lost,” he said.

“Now I live by routine, I train, eat well, go to bed at the same time.”

“Routine keeps me grounded.”

He acknowledged how far the NRL has come in supporting mental wellbeing.

“When I started, the attitude was ‘toughen up.’”

“Now the NRL’s come a long way, there are welfare managers, psychologists, people checking in,” he said.

Still, he said, the game can do more.

“We need to make players feel comfortable being who they are, whatever that means for them.”

“No one’s really thinking about you, everyone’s got their own problems.”

“We need to make the game a safe space for everyone.”

Cordner also reflected on the emotional pressure of leadership.

“When someone talks to you, sometimes you just need to listen, not fix them, just be there,” he said.

“I’ve been on the floor myself, broken.”

“I know what it’s like to want someone to just sit with you.”

“The people who made the biggest difference weren’t the ones with the answers, they were the ones who didn’t judge.”

“You never know what someone’s carrying, so be the person who gives them space to breathe.”

He spoke candidly about the unseen cost of professional sport.

“The physical side of rugby league is one thing, but the mental side, that’s what really tests you.”

“You can be the fittest bloke in the room, but if your mind isn’t right, you’re gone.”

Cordner also addressed the fear and stigma that still exist in sport and society.

“There’s still fear,” he said.

“Fear of speaking up, fear of being judged, fear of being different.”

“When someone comes out as gay or bi in our sport, that’s courage.”

“We have to make people feel safe to be who they are, no matter who that is.”

“We’re getting better, but we’re not there yet and there’s still more to do.”

He ended with gratitude and purpose, saying, “I’m grateful for everything, even the pain, because it’s made me who I am.”

“If I can share my story and one person feels less alone, then it’s worth it.”

“We don’t talk about this stuff enough, but the more we do, the more people realise they’re not broken, they’re just human,” Cordner said.

If you or someone you know is struggling, please reach out for support, Young Medicare Mental Health Centre is available at 02 6453 4440.

You can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636 for confidential help at any time.